Hi, I’m Sara de Rose – the inventor of the Musicircle and the author of this website, including academic material relating to the Mesopotamian musical system.

Here’s the story of how I created the Musicircle and became involved in the field of music archaeology.

I was born in the mid 1960s in Toronto, Canada. As a child, I took lessons with the neighborhood piano teacher. Then, as a teenager, I picked up the guitar.

The more I played, the more I wanted to know about music theory. In looking for patterns, I made a list of the keys with 0, 1, 2, etc., … sharps (C, G, D, etc.,), coming out with what I later learned is called the circle of fifths.

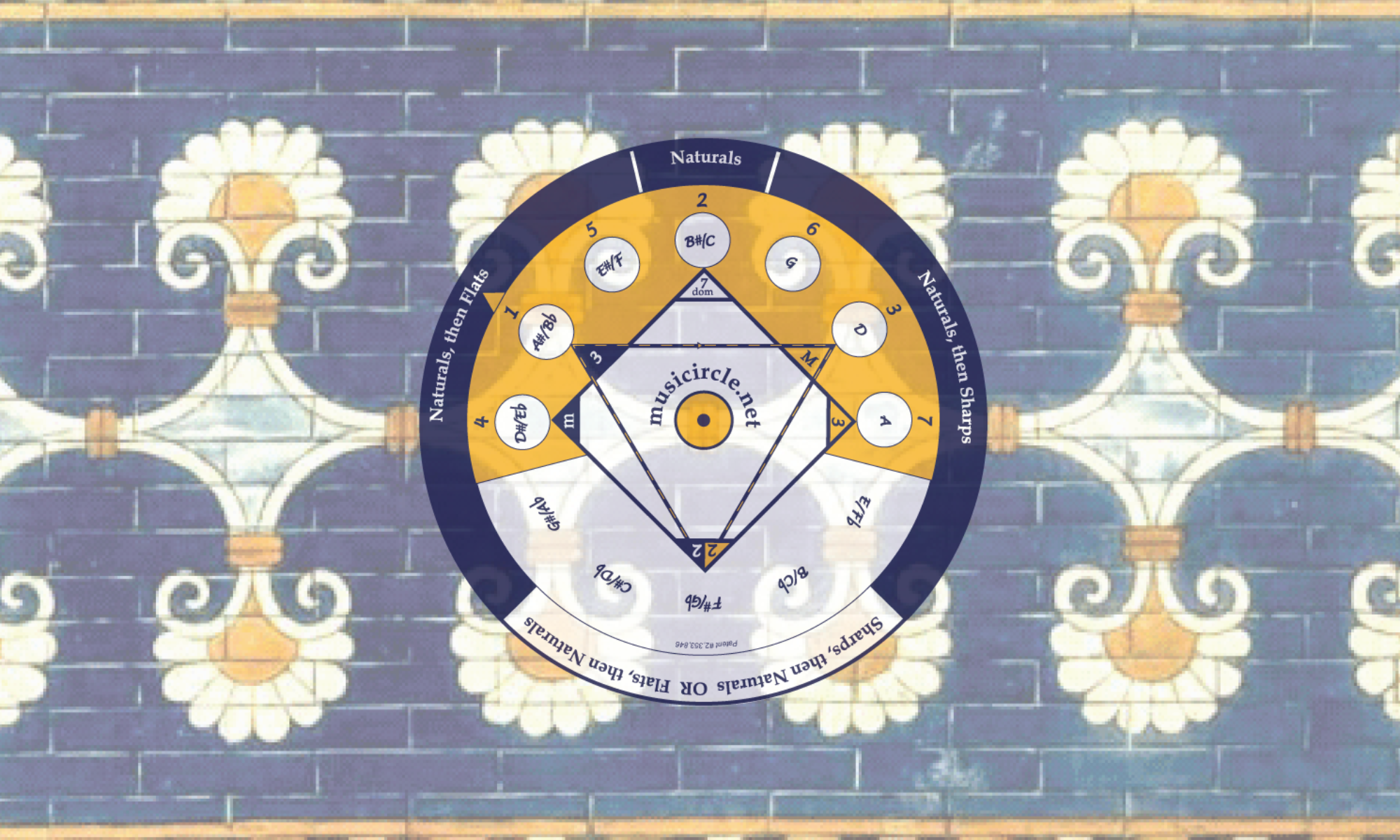

Over the next ten years, I continued to explore music theory using the circle of fifths, creating what I came to call the Musicircle: adding to the circle of fifths (1) the keyfinder (the yellow shape that gives the notes in scales and modes), (2) the chordfinder (the centre shape, that gives the notes in all types of chords), and (3) the outer rim (that indicates how to name the notes in scales and chords).

In my twenties, I settled on a remote island off the West Coast of Canada. There, I began to study the cycles of the sun, the moon, and the visible planets: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. What I experienced (and what our ancestors throughout the ages experienced) is the illusion that the earth is stationary and that these seven bodies circle the earth. In other words, through direct observation, I became familiar with the ancient model of the universe.

One evening, I lay in bed working out a theory question with the Musicircle. When I was done, I put the Musicircle beside my bed and my mind went on to other things – one of which was wondering at the order of the days of the week. I had recently learned that the days are named after the sun, the moon and the five planets visible planets. But why, I wondered, are the days arranged in this particular order?

I woke up in the night and imagined giving each of the seven “ancient” planets a number, depending on its apparent speed. Because the moon appears to move most quickly through the constellations, I gave it the number 1. Then, I gave Mercury, the number 2, because it appears to move second fastest. And so on: Venus, number 3; Sun, number 4 (because it appears to move at the relative speed of the earth), Mars, number 5; Jupiter, number 6 and Saturn, number 7.

But the week isn’t ordered this way: for example, Moon day (Monday) comes after Sun day (Sunday). So, I listed the numbers I had given the ancient planets, but this time in the order given by the week.

I began with Sunday, because Sunday is traditionally the first day of the week: #4 (the sun), #1 (the moon), #5 (Mars), etc. Listing all seven bodies, I came out with the sequence 4,1,5,2,6,3,7. I was amazed…because this is the sequence of numbers on the Musicircle. How was this possible? Was there some connection between the major scale and the week?

I had to find out. Because the sequence 4,1,5,2,6,3,7 selects the notes in the major scale from the circle of fifths, I decided to explore the origin of the circle of fifths. I soon learned that musical intervals are heard by shortening a string to specific lengths: to hear the octave, you play 1/2 of the string; to hear a fifth, you play 2/3 of the string, …

Then I learned that you can play the fifth of the fifth, by playing 2/3 of 2/3 of the string, and that you can do this repeatedly. I soon understood that this is the origin of the circle of fifths: it is a circle of 12 notes, each one the fifth (and therefore having 2/3 of the string length) of the note before it. To learn more, watch the video The Origin of the Circle of Fifths.

I then learned that Pythagoras is said to have created a scale using only the intervals of the octave and the fifth (although I now know that the Mesopotamians did this over a thousand years before Pythagoras). So, taking a strip of paper the length of my guitar string, I folded it using the fractions 1/2 and 2/3 to create notes, represented by the fold lines. After creating 12 folds or “notes,” in the circle of fifths order, I came out with the pattern of the frets on the guitar fret board. Most amazingly, this paper-folding exercise generates the sequence 4,1,5,2,6,3,7.

My folded paper fret board was a linear model, but I was used to working with the Musicircle, a circular model. This made me wonder if I could convert my paper fret board into a circular model. I did this in 2001, creating a seven-pointed star, with points numbered 1 to 7, that rotates on the circle of fifths.

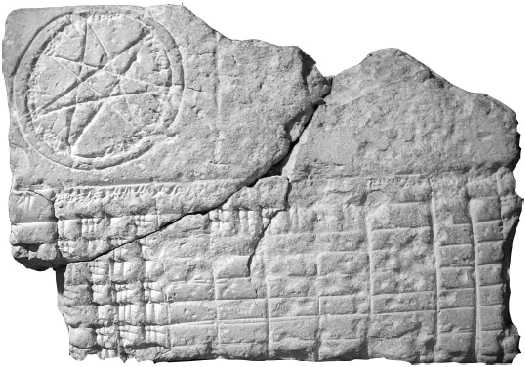

Now I jump ahead in my story 15 years, to 2016 and the moment when I first saw a photo of Mesopotamian tablet CBS 1766. On this 3000-year-old tablet is drawn a seven-pointed star, virtually identical to the one I drew in 2001. In a table drawn on the tablet are written inversions of the sequence 4,1,5,2,6,3,7. At the points of the star are written the names of the strings of the Mesopotamian lyre.

After seeing the photo of CBS 1766, I wrote a description of how the diagram and the sequence 4,1,5,2,6,3,7 can both be derived from the simple mathematics of music. I sent this description to a music archaeologist working in the field of Mesopotamian music and was invited to present my work at a conference in London, England. In the following year, my work was presented at an international conference in Germany.

In 2019, I learned that, as early as the 3rd century BC, the ancient Chinese used the equivalent of the paper folding exercise (calling it the sanfen sunyi method) to create a 12-tone scale. This, and other archaeological evidence of west-east musical contact between China and Mesopotamia, as early as 1000 BC, inspired me to write the paper “A Proposed Mesopotamian Origin for the Ancient Musical and Musico-Cosmological Systems of the West and China,” published by Sino-Platonic Papers, a journal founded by Victor H. Mair, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

In this paper, I discuss the similarity between the musical systems of the West, China, and Mesopotamia. I also discuss the relationship between music and cosmology in the ancient world, showing that, in the West, there is evidence for a tradition that used the musical sequence 4,1,5,2,6,3,7 to create various “cosmic correlations.”

One of these correlations – which I stumbled upon in 2001 – is the ordering of the days of the week. To quote the Roman historian Cassius Dio (155–235AD), who wrote about the reason for week-day order:

“…if you apply the so‑called “principle of the tetrachord” (which is believed to constitute the basis of music) to these stars [i.e., planets] …you will find all the days to be in a kind of musical connection with the arrangement of the heavens.”

The sequence 4,1,5,2,6,3,7 and the major scale were known to the Mesopotamians as early as 1800 BC. Over the next 2000 years, the sequence took on spiritual significance, and the musical scale came to symbolize a ladder (Latin ‘scala’: the root of the musical term scale) that was believed to provide a means for the soul to ascend to the heavens.

For example, two thousand years ago, during an initiation ritual of the Mithraic Mysteries initiates climbed a ladder of seven rungs, each rung representing a planet. The planetary rungs were arranged by the sequence 4,1,5,2,6,3,7.

Celsus, the second century Greek philosopher who documented this ritual wrote that “the reason of the stars [i.e, planets] being arranged in this order…[comes from]…musical reasons…quoted by the Persian theology.” This makes sense, because Persia was the neighbor of Mesopotamia and is believed to have used the same musical system. To learn more, read my paper “A Proposed Mesopotamian Origin for the Ancient Musical and Musico-Cosmological Systems of the West and China.”

Victor H. Mair, the founder of Sino Platonic Papers (the journal in which de Rose’s paper is published) who, among other things, is renown for his archaeological work on the Tarim mummies, says the following about de Rose’s work:

“Sara de Rose has made a tremendous breakthrough in the study of ancient east-west cultural communications. Professor Lothar von Falkenhausen, eminent archeologist and musicologist at UCLA, has this to say about Sara’s work: “Using sources previously unavailable, the article brings the two traditions closer together than ever before, and it certainly goes some way toward tipping the balance for the argument to diffusion over independent invention.” He goes on to explain: “The principal portion of the article, showing the mathematical-musicological parallels between tone-generation methods in ancient Mesopotamia and early China are extremely interesting and well presented. With respect to showing these parallels, and pointing out concrete structural similarities between China and Mesopotamia, it seems to me that the author is really making an important contribution.” ”

Professor Mair goes on to say “Sara’s opus is one of the most important papers we have ever published in SPP. Knowing something about Sara’s life story, all the more I consider her to be a genuinely clairvoyant genius.”

An abridged version of Sara’s paper, ideal for the general reader, is available here: “A Proposed Mesopotamian Origin for the Ancient Musico-Cosmological Systems of the West and China.”

I believe that this ancient tradition linking music and the ascent of the soul explains the intent behind the musical ordering of the days of the week: it was meant, I think, to ensure that the collective soul of the human race, by living through time, would ascend through the heavens to meet and merge with the divine.

What a beautiful vision to contemplate, as we live through the days of our lives…

4,1,5,2,6,3,7