A handful of 3000 to 4000 year-old cuneiform tablets deciphered since 1960 show that the major scale originated in Mesopotamia.

Tablet UET VII 126 dates from approximately 600 BC, but is believed to be a copy of an older tablet because a fragment from 1800 BC duplicates some of the information.

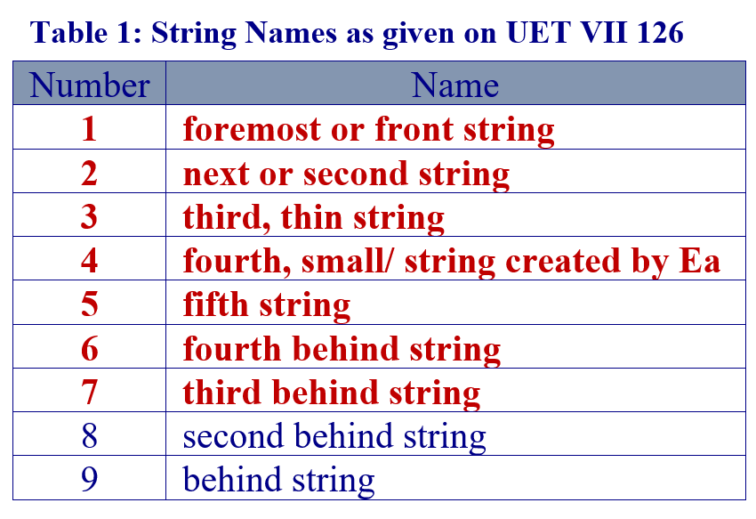

UET VII 126 lists the nine strings of the sammu, the Mesopotamian lyre. The nine strings were named, by the Mesopotamians, by counting inwards from the front and back of the instrument towards the middle, and their names reflect this. A translation of UET VII 126 is given in Table 1.

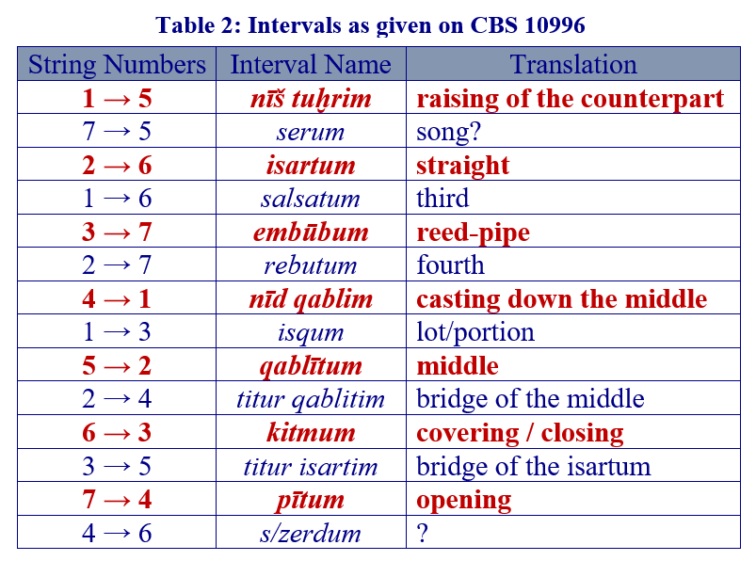

The names of the first seven strings (those in red in Table 1) were used to describe fourteen different intervals, as is shown by the next tablet: CBS 10996.

CBS 10996, which dates from approximately 700 BC, lists fourteen intervals. Each of these intervals is heard by sounding two of seven of the strings of the sammu (those in red in Table 1). The Mesopotamian names for these intervals are given on CBS 10996. For example, the interval heard between string 5 and string 2 is called qablītum (see Table 2).

CBS 10996 lists fourteen intervals. However, the tuning instructions on UET VII 74 (the next tablet) only refer to seven of these intervals (those shown in red in Table 2). Consequently, music archeologists refer to these seven intervals as ‘primary.’

Notice that the string pair numbers of the primary intervals in Table 2 generate the sequence 1,5,2,6,3,7,4, two times. This sequence is also embedded in the tuning instructions on tablet UET VII 74.

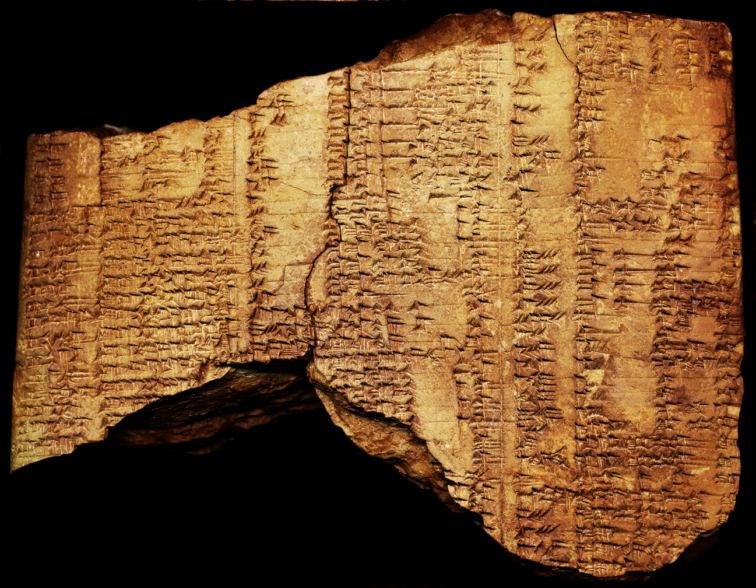

UET VII 74, which dates from approximately 1800 BC, describes how to tune the sammu to seven different tunings by referring to the seven primary intervals listed on CBS 10996.

The instructions refer to nine strings, explaining that string 8 must be tuned with string 1 and that string 9 must tuned with string 2. This led music archeologists to deduce that strings 8 and 9 are octaves of strings 1 and 2, respectively and, therefore, that the Mesopotamians used a seven-note scale.

They also deduced that this scale was diatonic (i.e., that it had the same structure as the major scale we use today), because the sequence 1,5,2,6,3,7,4 (found on UET VII 74, CBS 10996 and the next tablet: CBS 1766) has a fundamental relationship to the diatonic scale.

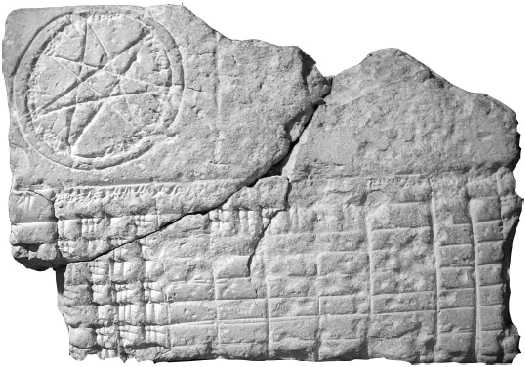

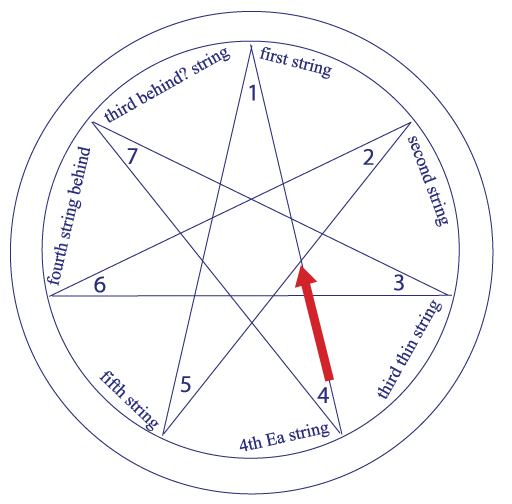

CBS 1766 dates from the first millennium BC. On the tablet is drawn a seven-pointed star, at the points of which are written the seven string names of the lyre shown in red in Table 1. The points of the star are also labelled with the numbers 1 to 7, in a clockwise direction. Following the diagonals of the star generates the inversions of the sequence 1,5,2,6,3,7,4. For example, 4,1,5,2,6,3,7 (see drawing).

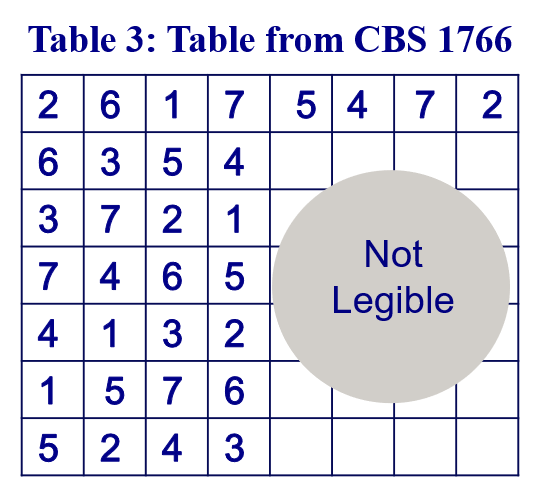

In the table below the star are written the sequence 1,5,2,6,3,7,4 and its inversions (see Table 3).

If you would like to learn more about the Mesopotamian musical system and how modern music theory is derived from this system, host an interactive workshop for your colleagues or students.

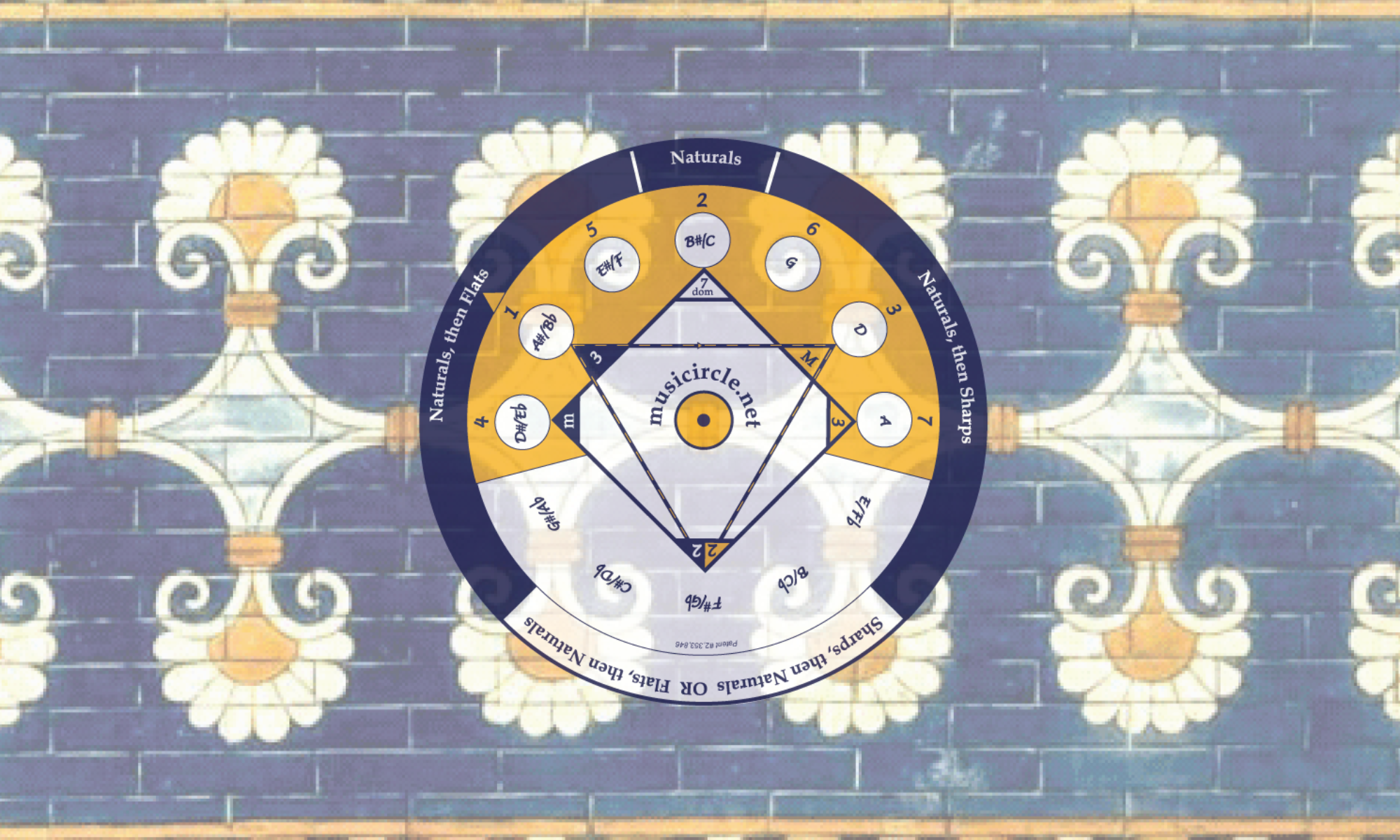

The keyfinder of the Musicircle is printed with the numbers 4,1,5,2,6,3,7, an inversion of the sequence 1,5,2,6,3,7,4. The Musicircle was invented and patented before CBS 1766 was known to relate to music. Since becoming aware of CBS 1766 in 2016, Sara de Rose, the inventor of the Musicircle, has played a role in explaining the mathematical origin and musical applications of the star.

According to Dr. Richard Dumbrill, Director of the International Council of Near Eastern Archaeomusicology, Sara’s work is “the missing link between linear and circular concepts, and also the link between Mesopotamian and Greek constructions during the Orientalising period (800-600 BC)”

According to John Franklin, Head of the Classics Department of the University of Vermont and a leading music archaeologist: “Sara de Rose’s work integrates, into modern music education, our knowledge of the ancient Mesopotamian tuning tradition…Her materials and approach are a very effective way to help students understand…the cuneiform tablets. I enthusiastically endorse the integration of her material into any course of musical study.”

To understand more about the Mesopotamian musical system, read the paper “A Proposed Mesopotamian Origin for the Ancient Musical and Musico-Cosmological Systems of the West and China,” published by Sino-Platonic Papers, a journal founded by Victor H. Mair, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

You can also read academic papers by other scholars in the field here.